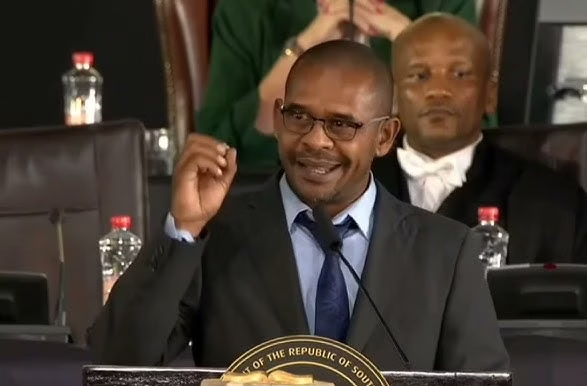

The controversy surrounding Lieutenant-General Nhlanhla Mkhwanazi has deepened after a criminal charge of perjury was formally lodged against him, following his retraction of serious allegations made against former police minister Bheki Cele. The complaint, filed at Cape Town Central Police Station, was initiated by National Coloured Congress (NCC) leader Fadiel Adams on Tuesday morning.

Retraction Sparks Parliamentary Outrage

According to Adams, Mkhwanazi’s decision to withdraw his explosive claims through a simple SMS was met with disapproval from Members of Parliament, who insisted he return to the parliamentary committee to formally retract his sworn statement. The informal nature of his retraction, they argued, failed to match the gravity of the original allegations made under oath.

Western Cape police spokesperson Sergeant Wesley Twigg confirmed that a case had indeed been opened.

“The mentioned case number is a perjury case registered at Cape Town Central SAPS. The identity of those concerned are not released,”

said Twigg.

Efforts to obtain comment from KwaZulu-Natal police spokesperson Robert Netshiunda on whether the province’s authorities were aware of the perjury case remained unanswered at the time of publication.

Allegations That Shook SAPS Leadership

Mkhwanazi’s initial testimony before the Madlanga Commission sent shockwaves through the South African Police Service. He alleged that Bheki Cele had provided a bank account to attempted murder-accused tenderpreneur Vusimuzi “Cat” Matlala, into which funds were allegedly deposited. These claims drew intense scrutiny due to their implications for the integrity of both the police and government institutions.

However, in a striking reversal, Mkhwanazi later withdrew his allegations, admitting that his team had identified the wrong bank account. In his retraction, he expressed remorse, saying he apologised to Cele for

“any inconvenience or hurt caused.”

Adams Responds With Legal Action

For Fadiel Adams, the retraction was not enough. In an affidavit accompanying his complaint, he highlighted the potential damage caused by the general’s public claims.

“Such statements have the potential to erode public trust in SAPS leadership and create confusion regarding official investigations. I further express concern that if such false allegations were made publicly against a Minister, other persons may also be falsely accused by General Mkhwanazi without substantial evidence. These false public allegations still constitute serious misconduct and possibly a criminal false accusation (defamation or defeating justice),”

he wrote.

Adams also referenced a statement from the Judiciary of South Africa, which weighed in on the controversy.

“Subsequent to the retraction or apology made by Lieutenant General Mkhwanazi, the Judiciary of South Africa issued a media statement noting that General Mkhwanazi’s ‘claims, made without substantiation, are extremely damaging to the public confidence in the independence and integrity of our courts’.”

Intelligence Dispute Fuels Further Tension

The fallout has not been confined to Cele alone. During the Madlanga Commission, Mkhwanazi accused Adams of having handled criminal intelligence “recklessly.” He asserted that the classified material in question had been intended only for vetted members of the Joint Standing Committee on Intelligence, the parliamentary body charged with overseeing the country’s intelligence services.

Adams, who is not a member of that committee, dismissed the accusation as hypocritical. Speaking on Tuesday, he remarked:

“Mkhwanazi has an issue with me having obtained top secret information. He is talking top secret information in the Madlanga Commission without having the relevant security clearance.

The provincial commissioner does not have top secret classification which means he is not supposed to receive top secret classified documents. Which means he can’t dispense a budget properly, he can’t give a directive properly because he does not have access to top secret information. Or does he? Is he guilty of the same thing he is accusing me of. This man is a walking contradiction,”

said Adams.

Questions Over Credibility

Adams acknowledged uncertainty about whether Mkhwanazi’s retraction would alter the nature of the accusations made against him personally, but he made his stance clear:

“I am concerned about the credibility of the man.”

At face value, both actions — Lieutenant-General Nhlanhla Mkhwanazi’s alleged “whistleblowing” before the Madlanga Commission and Fadiel Adams’s reported handling of top-secret information — involve the disclosure of sensitive material. Yet, legally and ethically, they differ in purpose, procedure, and consequence.

Whistleblowing Versus Breach Of Secrecy

Whistleblowing, in principle, refers to the act of exposing wrongdoing, corruption, or misconduct within an institution, often in the public interest. South African law, through the Protected Disclosures Act (No. 26 of 2000), offers protection to individuals who reveal information about corruption or unlawful acts, provided their disclosure is made in good faith, with reasonable belief, and through proper channels.

Mkhwanazi, in his testimony before the Madlanga Commission, appeared to frame his statements as an attempt to reveal alleged corruption — particularly involving former minister Bheki Cele and financial transactions linked to an accused tenderpreneur. Had these claims been substantiated, and made through appropriate processes, they could arguably fall under the scope of whistleblowing.

However, the crucial issue is accuracy and intent. When Mkhwanazi later retracted his allegations, admitting that his team had misidentified a bank account, it severely undermined the credibility and good faith element that whistleblowing requires. In law and ethics, a false or unsubstantiated accusation does not qualify as protected disclosure — it becomes a potential case of defamation or perjury, as alleged by Adams.

Handling Of Classified Information

Adams’s alleged conduct, on the other hand, centres on the possession and use of top-secret information without authorisation. This falls under a very different legal framework — notably the Protection of Information Act (1982) and the National Strategic Intelligence Act (1994) — both of which strictly govern access to, and disclosure of, classified state material.

Unlike whistleblowing, which can be protected if done lawfully and in the public interest, the unauthorised handling of classified intelligence is a security breach, regardless of motive. Even if Adams accessed such information to expose wrongdoing, the absence of formal clearance or lawful procedure could render his actions illegal, exposing him to prosecution under national security laws.

A Case Of Intent, Process, And Accountability

The difference, therefore, lies not only in what was revealed but in how and why it was revealed. Mkhwanazi’s disclosures, though framed as whistleblowing, became problematic because they were incorrect and later withdrawn — suggesting negligence or recklessness rather than deliberate corruption exposure. Adams’s case, meanwhile, raises questions of procedure and accountability — whether his use of classified material, even if for oversight purposes, violated established laws of secrecy.

Both men now stand in a legal and moral grey area: one accused of making false claims under oath, the other accused of mishandling confidential state material. Each defends his actions as being in the public interest, yet both risk undermining the very institutions — the police and Parliament — they claim to protect.