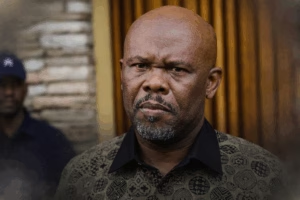

The quiet airfields of South Africa, where small aircraft enthusiasts often gather, once played host to Timothy James Clark. To those who knew him at Stellenbosch airfield, he appeared to be nothing more than a friendly Australian with a scruffy head of hair and a passion for flying. What few realised was that behind the easy laughter and casual chatter, Clark lived a very different existence, one that placed him at the centre of international cocaine smuggling operations.

A Familiar Face With a Hidden Agenda

Locals remember Clark’s regular visits in his Sling aircraft. He would arrive like any other hobby pilot, joke with those around him, and arrange for his plane to be serviced at the Sling factory in Alberton. Yet his so-called pastime was anything but harmless.

“Little did anyone know that his hobby was cocaine smuggling on a grand scale.”

The 46-year-old’s last flight ended abruptly in Brazil this week. His small Sling 4 went down in a sugar cane field near Couripe on the coast of Alagoas, with 200 kilograms of cocaine on board. The haul carried an estimated street value of R920 million, edging close to the R1 billion mark.

Police Pursuit Across Skies

Brazilian police had long been monitoring his movements. Clark flew low, often without a transponder, which made tracking him an exhausting task. This time, however, officers were close behind when his aircraft came down.

Sources in aviation circles suggest Clark had crossed the Atlantic repeatedly in that same Sling, transporting drugs between South America and Africa. Cargo was offloaded in Namibia and South Africa, and the aircraft would then return to Brazil to collect more. His final flight was, by all indications, another of these transcontinental runs.

One element drew particular attention: the packages of cocaine bore SpaceX branding.

“That’s because illicit drug manufacturers often copy well-known logos to camouflage the real deal.”

The Finances of a Smuggling Operation

The scale of Clark’s operation was staggering. For each successful trip, he reportedly received around R8.6 million. The Sling 4 had been modified extensively for the purpose, with three of its four seats stripped out and replaced by long-range fuel tanks, all installed in Alberton. The hidden compartments provided space for large drug consignments while ensuring the aircraft could manage its long journeys across the Atlantic.

Records show that Clark purchased the Sling three years ago, registering it with the South African Civil Aviation Authority under a company called Mindframe Creations. Its listed director, Raza Muhammad, has since become uncontactable. Aviation insiders believe Clark also kept a Beechcraft King Air 350 for legitimate flights, although the fact that it carried a Malawian registration number raised further suspicion.

According to industry estimates, the Sling had clocked 1,200 hours since Clark bought it. Considering each trip from Brazil to South Africa took about 40 hours, this suggested he may have completed around 30 Atlantic crossings. Even if he was only serving as a courier, his earnings could have exceeded R258 million.

A Businessman’s Background

The Daily Mail traced Clark’s earlier life in Australia, where he was listed as director and secretary of several investment businesses. These included Stock Assist Group Pty Ltd and Gurney Capital Nominees Pty Ltd, both of which remain registered. Other ventures such as Tjc Nominees Pty Ltd, Bluenergy Asia Pty Ltd and Tick-Tack-Toe Pty Ltd have either been cancelled or deregistered in recent years.

Colleagues and acquaintances often struggled to reconcile the man they met with the criminal empire he was building.

“If you saw him on the street, you wouldn’t have thought for a moment that he had much money,” said a source.

“He was a typical, somewhat scruffy Aussie with messy hair and old clothes, but then he would wear an extremely expensive pair of shoes. He spoke with relish about how he enjoyed the aircraft while flying around the world. None of us suspected he was actually involved in drug smuggling.”

A Life Between Two Worlds

Clark’s social media painted a picture of glamour and indulgence. Photos showed him in tuxedos with white gloves, handing out trophies, mingling with women, and lounging in clubs from Cape Town to Bali. It was a striking contrast to the reality of his high-risk flights, ferrying narcotics across continents.

Behind the façade was a man who had used his love of aviation as a cover. The repeated trans-Atlantic trips, the technical modifications to his aircraft, and his ability to stay one step ahead of law enforcement pointed to a network that had grown accustomed to exploiting Southern Africa as a landing point for cocaine.

South Africa’s Growing Vulnerability

Experts say his activities fit into a wider pattern. Julian Rademeyer from the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime noted worrying signs in the Western Cape.

“Saldanha has more recently also increasingly become the turf of gang violence, which is usually an indication of more drugs in the area.”

Clark’s Sling was also sighted in Namibia, and reports suggest that Mozambique formed another link in the smuggling chain. These movements highlight how Southern Africa is increasingly being used as a staging ground for narcotics headed elsewhere.

The End of a Double Life

Ultimately, Clark’s string of daring flights came to an end in a cane field in Brazil. Despite his years of evading the authorities, his operation collapsed in dramatic fashion, leaving investigators to piece together how a man who seemed ordinary at first glance had become such a significant player in the international drug trade.

The picture that emerges is one of contradiction: a disheveled Australian pilot on the surface, yet in reality a wealthy courier for powerful networks moving drugs across the globe. His story underscores the hidden routes and quiet airfields that make Southern Africa vulnerable to exploitation by international syndicates.