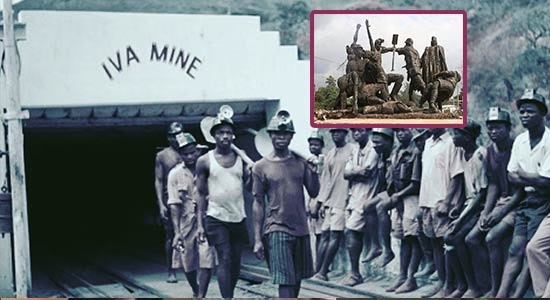

The ruling by a Nigerian court ordering the British government to pay £420 million in compensation has reopened one of the darkest chapters in the country’s colonial past. The judgment centres on the killing of 21 coal miners in 1949 at the Iva Valley Coal Mine in Enugu, an incident that has lingered in Nigeria’s collective memory as a brutal symbol of imperial power exercised without restraint.

At the time, the miners were protesting against poor working conditions, demanding dignity and basic labour protections rather than confrontation. Colonial police responded with lethal force, opening fire on workers who were occupying the mine. The deaths reverberated far beyond Enugu, galvanising nationalist sentiment and helping to fuel the independence struggle that culminated in Nigeria’s liberation from British rule in 1960.

Judge Condemns Use Of Lethal Force

Justice Anthony Onovo of the Enugu High Court delivered a scathing assessment of the actions taken by British security forces. His ruling rejected any suggestion that the miners posed a threat, framing the killings as an unjustified and disproportionate act of colonial violence against unarmed workers seeking redress.

These defenseless coal miners were asking for improved work conditions. They were not embarking on any violent action against the authorities, but yet were shot and killed.

Decades Long Struggle For Recognition

The judgment marks the culmination of a legal and moral battle that has stretched across generations. For decades, families of the victims pursued acknowledgment and accountability, often in the face of silence or indifference. The case has been viewed within Nigeria not merely as a compensation claim, but as a demand for historical truth and institutional recognition of colonial-era abuses.

Many historians regard the Iva Valley killings as a turning point, one that exposed the contradictions of colonial governance and hardened resistance to foreign rule. The court’s decision effectively validates that historical interpretation, affirming that the events of 1949 were neither accidental nor defensible within any lawful framework.

Nigerian State Found Wanting

In a notable aspect of the ruling, Justice Onovo criticised the Nigerian government itself, stating that it had failed in its constitutional responsibility to pursue justice on behalf of its citizens. This finding adds a contemporary dimension to the case, highlighting how post colonial administrations have sometimes neglected unresolved injustices inherited from imperial rule.

The judgment suggests that accountability is not solely external, but also internal, placing a moral obligation on Nigerian institutions to actively protect historical memory and the rights of victims. The court’s remarks carry implications for how the state approaches other unresolved cases linked to colonial exploitation and violence.

Legal Victory Framed As Moral Reckoning

Lawyers representing the families of the slain miners described the ruling as a watershed moment. They framed it not only as financial compensation, but as a legal acknowledgment that colonial abuses remain subject to scrutiny and redress, regardless of the passage of time or changes in sovereignty.

Historical accountability and justice for colonial-era violations

reaffirmed that the right to life knows no borders or changes in sovereignty

Silence From London

The British government declined to comment on the ruling, and no representatives from the United Kingdom took part in the court proceedings. That absence has been noted by observers as emblematic of a broader reluctance to engage with colonial-era claims that challenge long standing narratives of empire.

Whether the compensation order will be enforced remains uncertain, but the judgment itself has already altered the legal and political landscape. For many Nigerians, it represents an overdue reckoning, a formal declaration that colonial violence carries consequences, even generations after the blood was spilled.