As South Africa edges closer to Parliament’s decisive budget vote, the African National Congress (ANC) finds itself in an increasingly precarious position. Facing widespread criticism for its push to raise Value-Added Tax (VAT), the ruling party must now reckon with both economic implications and a shifting political landscape—one that may reshape voter allegiance and test the strength of fragile alliances.

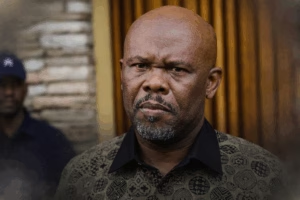

In a revised budget presented on 12 March, Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana proposed a tempered VAT increase, reducing the originally planned two-percentage-point hike to one, staggered over two years. Nevertheless, the proposal was met with broad resistance from opposition parties across the parliamentary spectrum.

Historically, the ANC has relied on its majority in Parliament to pass budget measures with little resistance. But recent years have seen a dramatic erosion of that dominance. Now forced into cooperative governance, including a tenuous arrangement with the Democratic Alliance (DA), the party faces mounting pressure to secure support from parties such as the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) and the uMkhonto weSizwe Party (MKP).

Independent political analyst and University of Limpopo senior lecturer Dr Metji Makgoba raised concern about the ANC’s strategy and the potential fallout for its prospective allies.

“If the EFF and MKP decide to enter discussions with the ANC but fail to oppose the VAT hike, they too risk severe political consequences,”

he cautioned.

“Both parties have built their platforms on advocating for economic justice and supporting the interests of the poor. Supporting a tax increase disproportionately affecting their constituencies could undermine their credibility and erode their support base.”

The ANC, long viewed as a party of the people, is now under fire for advancing a policy that critics argue disproportionately affects those same communities. While the party frames the VAT increase as a necessary fiscal adjustment, detractors question whether it aligns with the ANC’s professed commitment to pro-poor governance.

“By advocating for a tax increase that disproportionately impacts the working class and lower-income groups, the ANC risks alienating its core voter base and undermining its legitimacy,”

said Makgoba.

He further warned that the VAT issue is not simply a matter of fiscal policy, but a barometer for political authenticity and ideological resolve.

“This alignment with right-wing economic ideologies could weaken the ANC’s standing among working-class voters,”

Makgoba argued.

“By adopting a populist stance against the VAT increase, the DA positions itself as more responsive to the economic challenges faced by ordinary South Africans, despite its broader neoliberal policy framework.”

The DA’s rejection of the proposed VAT hike has forced the ANC into an increasingly defensive posture. This has complicated the party’s internal coherence, as it attempts to reconcile divergent economic ideologies within a fragile coalition government.

Former chairperson of the Standing Committee on Public Accounts (Scopa) and leader of the African People’s Convention (APC), Themba Godi, pointed to the impasse as indicative of a deeper political dilemma.

“It shows the ANC has no option because the DA is digging in and making political demands,”

Godi stated.

“The ANC is therefore forced to look at those parties it knows are pro-black and can reach agreements with.”

Godi suggested that the situation may prompt a reassessment of coalition arrangements altogether, particularly if the ANC continues to encounter resistance from the DA.

“This situation opens the door for possible future consideration of alternatives to the current coalition arrangement, where the ANC might find a more stable partnership with black parties rather than being beholden to the DA’s political decisions within the coalition,”

he added.

The EFF and MKP now face a critical test of their political resolve. With both parties rooted in discourses of social justice and economic empowerment, any perceived concession to a tax policy that burdens the economically vulnerable could have lasting implications for their political identities.

Makgoba warned that the risk of appearing politically expedient could alienate core supporters.

“Ultimately, how the ANC navigates this contentious issue will have significant ramifications,”

he said.

“If the party continues to advocate for the VAT increase despite widespread opposition, it risks deepening public disillusionment and accelerating its decline in electoral support.”

The ANC’s current strategy appears to hinge on short-term alliance-building to pass its budget while attempting to maintain a sense of fiscal discipline. Yet this comes at a time when rising poverty and inequality among black South Africans have made any form of regressive taxation especially sensitive.

With the VAT debate now unfolding as a proxy battle over ideological direction, party identity, and coalition stability, the stakes have escalated far beyond the immediate fiscal implications. As the budget vote looms just weeks away, the ruling party finds itself caught between economic necessity and political survival.

How Does an Increase in VAT Affect the Poor?

An increase in Value-Added Tax (VAT) tends to have a disproportionate impact on low-income households, and understanding why reveals much about the broader debate currently playing out in South African politics.

VAT is a consumption-based tax, meaning it is levied on goods and services at each stage of the supply chain and ultimately passed on to the consumer. In South Africa, the standard VAT rate is 15 percent, and although certain basic food items are zero-rated (not taxed), many essential goods and services are still subject to VAT.

For wealthier households, VAT represents a smaller proportion of their income because they tend to spend less of their earnings on consumables. In contrast, poorer households spend a higher percentage of their income on daily essentials, many of which are not zero-rated. This means that even a modest increase in VAT can effectively reduce their already limited purchasing power.

Consider a household earning near the poverty line: any rise in the cost of cooking oil, electricity, or transport—as a result of VAT—immediately cuts into their ability to meet other basic needs, such as education or healthcare. It is not merely about paying more; it is about choosing between essentials.

Moreover, in the context of rising unemployment, stagnant wages, and increasing food insecurity, a VAT hike becomes more than an economic adjustment—it becomes a political flashpoint. Critics argue it is a regressive tax, as it imposes a heavier burden on those least able to absorb it.

While government may argue that increased VAT revenue is necessary to plug fiscal holes or fund social programmes, the immediate effect on the ground—especially among South Africa’s most vulnerable—can be devastating.

This is why opposition to a VAT increase is not only about fiscal ideology but also about social justice. For parties like the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) and the uMkhonto weSizwe Party (MKP), which have built support on the promise of representing the poor, backing such a measure could be politically ruinous.

Thus, any proposed VAT increase must be weighed not just by its economic logic, but by its human cost.

Why Does the Government Not Increase Corporate TAX?

The question of why the South African government does not increase corporate tax—especially while considering a Value-Added Tax (VAT) hike that disproportionately affects the poor—is central to ongoing debates around fairness, fiscal policy, and political priorities.

At first glance, raising corporate tax might seem like a more equitable solution. After all, large businesses typically have broader shoulders and deeper pockets than low-income households. So why has government been hesitant to go down this path?

There are several interlinked reasons—some economic, some political.

Investor Confidence and Capital Flight

One of the primary reasons cited by government and treasury officials is the need to maintain investor confidence. South Africa is in fierce competition with other emerging markets for foreign direct investment (FDI). A sudden or significant hike in corporate tax could signal a less business-friendly environment, potentially deterring new investment or even prompting capital flight, where businesses shift their operations or profits offshore to avoid higher taxes.

In this sense, government walks a tightrope: it needs to raise revenue without creating a hostile environment for economic growth. Raising corporate tax could slow down investment, job creation, and long-term economic recovery.

South Africa’s Existing Corporate Tax Rate

South Africa’s corporate tax rate currently stands at 27 percent for most companies—a figure that is higher than the global average, particularly in many developing countries aiming to attract investors. Over the past few years, National Treasury has actually reduced the rate (from 28 percent to 27 percent in 2023) as part of a broader plan to make the country more competitive internationally.

The thinking is that a lower headline rate, coupled with the closure of tax loopholes and improved enforcement, could yield more sustainable revenue in the long run without choking the economy.

Tax Avoidance and Base Erosion

Another critical factor is the ease with which large corporations can exploit loopholes and shift profits to low-tax jurisdictions. The problem of base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) is a global one, and South Africa has been no exception. Increasing corporate tax without first strengthening enforcement mechanisms could paradoxically reduce revenue if companies respond by avoiding taxes more aggressively.

Thus, government may perceive VAT—which is collected at point of sale and harder to avoid—as a more reliable source of revenue.

Political Calculus

There is also a political dimension. Governments are often under pressure not just from the electorate, but also from influential business lobbies. These groups argue that raising corporate tax could lead to retrenchments, reduced investment, and lower economic growth—claims that carry weight in policy circles, especially in a country already struggling with high unemployment and sluggish growth.

In contrast, VAT—although deeply unpopular—can be implemented quickly, produces predictable revenue, and is seen by treasury as less economically disruptive, despite its regressive nature.

Could Corporate Tax Still Rise?

That said, there is growing pressure—both domestically and globally—for more progressive taxation. Civil society groups, labour unions, and even some economists argue that the burden of taxation in South Africa has shifted too heavily onto ordinary citizens, particularly the poor.

Increasingly, there are calls for the government to revisit not just corporate tax, but wealth taxes, capital gains, and other mechanisms to ensure the tax system does not entrench inequality. International reforms, such as the OECD’s push for a global minimum corporate tax, could also open the door for South Africa to revisit its position in the future.

For now, however, government appears to believe that increasing VAT is the most pragmatic—if politically risky—option in the face of rising fiscal pressure.

But that choice raises a critical question: is pragmatism sustainable when it comes at the cost of deepening inequality?