A group of Afrikaner families who relocated to the United States in May 2025 after being granted asylum on the basis of alleged discrimination and violence in South Africa arrived to what appeared to be an open embrace from senior American officials. Their landing at Dulles Airport outside Washington was marked by a formal welcome from Deputy Secretary of State Christopher Landau and Homeland Security Deputy Secretary Troy Edgar, in a moment that signalled diplomatic goodwill and humanitarian commitment.

At the airport reception, Landau addressed the newcomers with words that carried both reassurance and symbolism.

“I want you all to know that you are really welcome here and that we respect what you have had to deal with these last few years,” said Landau at the time.

For families who had uprooted their lives and crossed continents, the promise of stability, dignity and opportunity appeared within reach, anchored by commitments of structured government support.

Promises Of Structured Support

The United States government outlined a comprehensive support framework for the arrivals through the Office of Refugee Resettlement. The programme included initial housing placement, job assistance and school enrolment facilitation, delivered through accredited resettlement agencies funded by federal allocations. Legal entry was secured through documentation such as the Form I 94 Arrival Departure Record and Employment Authorization Documents, granting immediate work permission.

But didn’t @kalliekriel and them say Afrikaners have special skills? Or are they discovering just being a white person isn’t enough in the US😂 https://t.co/n3tVDluRY7

— BLMAlways (@ArsenalBLM) February 13, 2026

Financial safeguards were also presented as part of the transition package. Eligible refugees could access Refugee Cash Assistance and Refugee Medical Assistance for up to four months following their May 2025 arrival, with additional federal benefits such as Medicaid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program available to qualifying families. Within two years, refugees were entitled to file Form I 730 for family reunification, and after one year, they could apply for permanent residency through a Green Card, setting a formal pathway toward citizenship.

Reality Of Motel Living

Despite the framework presented, a recent report has cast doubt on the practical implementation of these commitments. Madeleine Rowley, a journalist with The Free Press, told CBS News that some families are now “barely scraping by”, raising concerns about systemic gaps within the resettlement apparatus. According to her reporting, at least ten families described weeks spent living in motels or in neighbourhoods they considered unsafe, while waiting for suitable accommodation.

Rowley indicated that federally funded resettlement agencies are mandated to secure safe, hygienic and reasonably priced housing. Instead, she reported that some refugees were offered apartments affected by mould or units located in high cost areas beyond sustainable budgets. In several instances, families alleged that attempts to contact assigned agencies went unanswered, leaving them dependent on informal assistance from neighbours.

Financial Strain And Uncertain Futures

Each refugee reportedly receives an initial allocation of $2,000, approximately R32,102, intended to ease early resettlement costs. However, interviewees told Rowley that most, if not all, of this amount has been absorbed by rental payments, leaving minimal funds for food, transport and other daily necessities. In high demand housing markets, even modest accommodation can command prices that rapidly erode limited start up assistance.

The strain is compounded by the time required to secure stable employment and navigate administrative processes in a new country. While legal work authorisation is granted upon entry, job placement depends on local market conditions, language proficiency and available networks. For families balancing childcare, schooling and unfamiliar systems, the gap between policy intention and lived experience has created mounting pressure, prompting questions about oversight and accountability within the relocation programme.

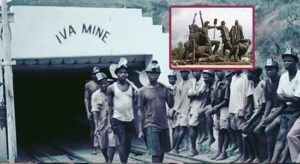

Manufactured Fear And The White Genocide Myth

The narrative of an organised white genocide in South Africa has circulated widely across certain political and social media platforms, often amplified by fringe commentators and partisan activists. Despite repeated investigations by credible institutions, crime analysts and academic researchers, there is no verified evidence of a state sanctioned or coordinated campaign targeting white South Africans as a racial group. Violent crime in the country remains a grave and complex crisis, affecting communities across racial and socio economic lines, yet the selective framing of isolated farm attacks as proof of genocide has taken root in some circles abroad.

For some of the Afrikaner families who chose relocation, the influence of emotive rhetoric and unverified claims may have shaped perceptions of imminent existential threat. Sensational messaging, frequently stripped of statistical context and broader crime trends, has created a climate where fear can eclipse fact. While concerns about safety are deeply personal and legitimate, conflating high crime rates with a narrative of racial extermination risks distorting reality and undermining informed public discourse, both in South Africa and internationally.