South Africa’s recent decision to reduce interest rates by 25 basis points has drawn sharp criticism from economist Dr Roulf Botha, who describes the move as “appalling” and insufficient to address the nation’s economic challenges.

Dr Botha argues that the current prime overdraft rate of 11.5% is unjustifiably high, especially when compared to pre-COVID levels. He notes that before the pandemic, “South Africa’s prime overdraft rate was 10%, and inflation was more or less exactly where it is now.” He contends that the elevated rates are stifling economic recovery and hindering job creation.

“It doesn’t make any sense, quite frankly, because this economy has not fully recovered yet from the COVID pandemic and from state capture.”

He emphasises that maintaining one of the highest real interest rates globally makes it impossible to stimulate growth:

“You cannot do that if your real interest rate… is amongst the highest in the world.”

Drawing comparisons with previous monetary policies, Dr Botha highlights the tenure of former Reserve Bank Governor Gill Marcus:

“When she was in charge, the average real prime rate was 3.1% during her term of office.”

In stark contrast, he points out:

“The real prime rate in South Africa today is 7.1%. It is an increase of 129%.”

He criticises the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) for prioritising inflation control over economic growth:

“They’ve lost sight of the second part of their mission statement, and that is to make sure that this economy grows.”

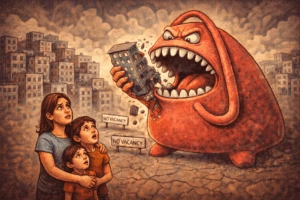

The high interest rates have significant repercussions for ordinary South Africans. Dr Botha notes:

“The percentage of debt cost expenses of the average household in South Africa is now 9.2% of disposable income. It is the highest in 15 years.”

He expresses concern over the increased financial strain on homeowners:

“Homeowners are now paying 4,000 rand a month, every month more, since the MPC started with this excessively restrictive monetary policy.”

This situation, he warns, is leading to dire consequences:

“People are losing their houses and we are not creating jobs.”

Dr Botha suggests that the MPC needs a broader perspective to better address the country’s economic needs. He proposes:

“They should seriously consider expanding the composition of the South African Monetary Policy Committee to also include seasoned veterans of economics in the private sector, and also the chief economist… of the National Treasury and of the Department of Trade and Industry.”

He believes this would lead to:

“A more balanced perspective on what monetary policy in this country should be.”

Many South Africans are sceptical about the impact of the 25 basis point reduction. Dr Botha describes the relief as minimal:

“Let’s call it Mickey Mouse. It helps… It certainly helps a little bit.”

However, he insists that more significant action is needed:

“Our interest rate remains way too high… There are so many indicators that are telling us that South Africa’s prime overdraft rate should be closer to 9%.”

Dr Botha highlights the lack of demand inflation and underutilised manufacturing capacity:

“There is no demand inflation in this economy… Capacity utilisation is still lower than it was before COVID.”

He argues that lowering interest rates would stimulate demand, leading to increased production and reduced overhead costs:

“With the increased demand, obviously your manufacturing capacity… will expand. That will mean that your supply side inflation will drop because your overhead unit costs will decline.”

Dr Roulf Botha is cooking here. “Monetary policy is the single biggest impediment to economic growth in South Africa.”

— Finance & economics (@Ndala_Momane) September 23, 2024